Captain America is square. He’s always been square, and he always will be square. It’s built into the DNA of the character. When Joe Simon and Jack Kirby launched the adventures of the Sentinel Of Liberty back in 1941, he was pure propaganda—a star spangled hero punching out the Axis Powers. Maybe that’s why, after the war ended, the character simply disappeared. “Old soldiers never die,” General Douglas MacArthur famously told a joint session of congress, “they just fade away.” It’s probably for the best that Cap faded away before the onset of the jingoistic, paranoid fifties. (A brief, failed attempt to reintroduce the character in 1953 as “Captain America…Commie Smasher!” gives us a glimpse of what we avoided.) When he made his reappearance in the Silver Age, he became the thawed out super soldier that we all know and love today: still square, sure, but more of a ‘roided up crime fighter than a political cartoon.

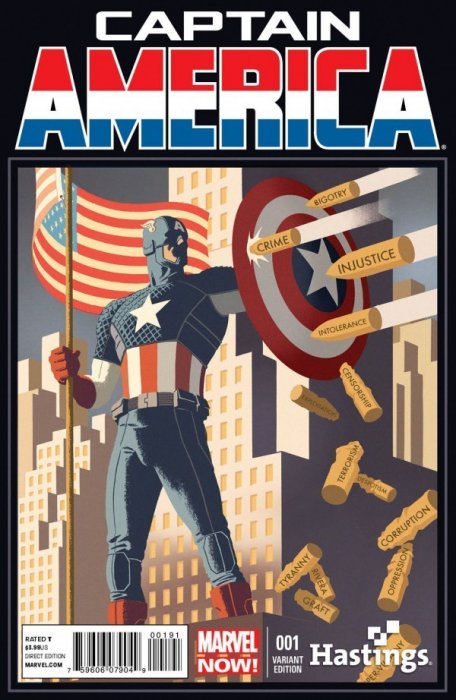

Even more than most comic book creations, however, Captain America has retained an intrinsic symbolic function. (All but unavoidable when half your name is America.) Over the years, various writers—Roger Stern, J.M. DeMatteis and Mark Gruenwald—have tapped his symbolic quality and used the character as a springboard to deal with various social problems (racism, extremism, homophobia), shaping him into one of Marvel’s most fascinating creations.

Some of the more interesting work on the character was done by Ed Brubaker in 2005 when he penned the now-classic Winter Soldier storyline. It did not come as a surprise to many fans of Captain America that Marvel Studios—once it had established the character in 2011’s Captain America: The First Avenger, and deployed him in 2012’s The Avengers—would turn to Brubaker’s sprawling political mystery as the basis for the next film, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, which hits theaters April 4th.

Some of the more interesting work on the character was done by Ed Brubaker in 2005 when he penned the now-classic Winter Soldier storyline. It did not come as a surprise to many fans of Captain America that Marvel Studios—once it had established the character in 2011’s Captain America: The First Avenger, and deployed him in 2012’s The Avengers—would turn to Brubaker’s sprawling political mystery as the basis for the next film, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, which hits theaters April 4th.

Brubaker’s The Winter Solider finds Steve Rogers in a bad mood. Foiling a terrorist attack on a train, Rogers is uncommonly brutal—snapping arms and grinding out threats through clinched teeth in a manner more reminiscent of Batman than Captain America. Asked about it by a concerned Agent 13, Rogers admits to feeling weighed down, haunted by bad memories:

You know what I see when I dream, Sharon? I see the war. My war. After all this time, I still dream about foxholes in the black forest… Still hear the screams of terrified soldiers. Smell their blood and tears… I still dream about Bucky. Him and all the others I couldn’t save…

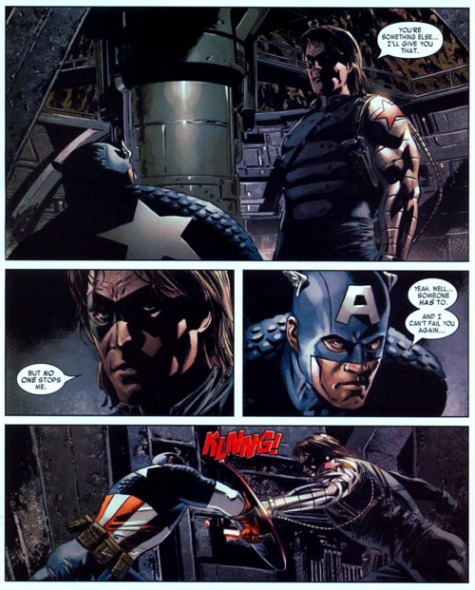

Bucky is, of course, Bucky Barnes, the childhood friend of Steve Rogers who would become Captain America’s sidekick during the war. What Rogers doesn’t know at the beginning of the Winter Solider saga is that Bucky—long thought dead—was captured by the Soviets and transformed into a shadowy super assassin. Unfolding over thirteen chapters (Captain America #1-9 and #11-14, with art by Steve Epting, Mike Perkins, Michael Lark, and John Paul Leon) the storyline spans the globe and several decades of the 20th century to culminate in a epic showdown between the old partners.

The best storylines in superhero comics almost always manage the neat trick of delivering expected pleasures with unexpected pleasures. On the expected pleasures front, we want to see our favorite characters being themselves. You want Spider-Man to be his smart-ass self, you want Batman to be brooding and intense. In this respect, comic book heroes are no different from other long-form narrative protagonists (Tarzan, Sherlock Holmes, Harry Potter). You buy a Captain America comic because Steve Rogers is a known entity and you like him. You know he’s a man defined by a largeness of spirit and a basic goodness. Of course, you also know that he has super-strength and can do some precision discus throwing with his vibranium shield.

The best storylines in superhero comics almost always manage the neat trick of delivering expected pleasures with unexpected pleasures. On the expected pleasures front, we want to see our favorite characters being themselves. You want Spider-Man to be his smart-ass self, you want Batman to be brooding and intense. In this respect, comic book heroes are no different from other long-form narrative protagonists (Tarzan, Sherlock Holmes, Harry Potter). You buy a Captain America comic because Steve Rogers is a known entity and you like him. You know he’s a man defined by a largeness of spirit and a basic goodness. Of course, you also know that he has super-strength and can do some precision discus throwing with his vibranium shield.

But the real key to a standout storyline concerns those unexpected pleasures. Anyone can write a story about Captain America thumping heads and bouncing his shield off walls, but a truly gifted writer finds a previously unexplored dimension of the character and seeks to do something new with it. What Brubaker finds in Steve Rogers is his sense of loneliness, the man out of time quality that has long been with the character but has rarely been exploited for emotional darkness. Brubaker takes a man of innate decency and puts him into the middle of a complicated (and, at points, convoluted) political landscape. The Winter Soldier is as much about crooked backroom political deals and shadow government operations as it is about explosions and fistfights. And this is a world where Steve Rogers doesn’t belong. Brubaker doesn’t give us a hero who easily overcomes this conundrum, he gives us a hero who struggles to find his footing, who reacts with rage and anguish at finding out that he’s being lied to on all fronts. When Steve finally comes face to face with Bucky, the pathos of the moment is that the Winter Soldier is really the only one who could hope to understand him.

We’ll have to wait and see what screenwriters Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely, and directors Anthony and Joe Russo do with their adaptation of this story. While no film could encompass the full breadth of Brubaker’s twisting tale, the filmmakers have publicly stated that they intend to stay relatively faithful to the books. Early buzz on the movie has been excellent—with Marvel Studios quickly signing the Russo brothers to helm the third Captain America feature. One thing is for sure: The Winter Soldier provides rich opportunities for the good captain.

Jake Hinkson is the author of the books Hell On Church Street, The Posthumous Man, and Saint Homicide. Read more about him at JakeHinkson.com. He also blogs at The Night Editor.